As the third lockdown begins, will the Chancellors £500 million additional funding for mental health support be enough to address the impact of Covid-19 on mental health and wellbeing?

A positive consequence of Covid-19 is that mental health now has a much higher national profile than it did pre-pandemic. The result of lockdown measures, damaging economic impacts, and a range of other negative consequences on people’s mental health, have been widely acknowledged.

However, the mental health impacts of Covid-19 will, for many, continue long after mass vaccination has suppressed the virus. Also, inequalities in mental health are growing, as the virus and its economic impacts continue to adversely affect specific groups and communities disproportionately.

Much of the demand for mental health support currently remains ‘deferred’, i.e. people have not yet sought help. The problem is storing up for the future. Before this buildup starts to be released, how should the mental health and broader care system prepare to respond, and will it be ready to cope with the surge in demand?

An opportunity to emerge stronger

Firstly, commissioners and providers should reset.

Mental health care in the NHS has been fragmented and relatively traditional in its approach. From planning, funding, and delivering services, there are many layers of bureaucracy. However well-intentioned, the consequence is significant variability in service quality.

A positive consequence of COVID-19 has been the opportunity to break previous norms and take a disruptive and system approach to rethink how mental health support and services are to be provided.

Good progress continues to be made in developing collaborative ways of working across organisations, but the pace needs to increase.

The surge in demand – how big and when?

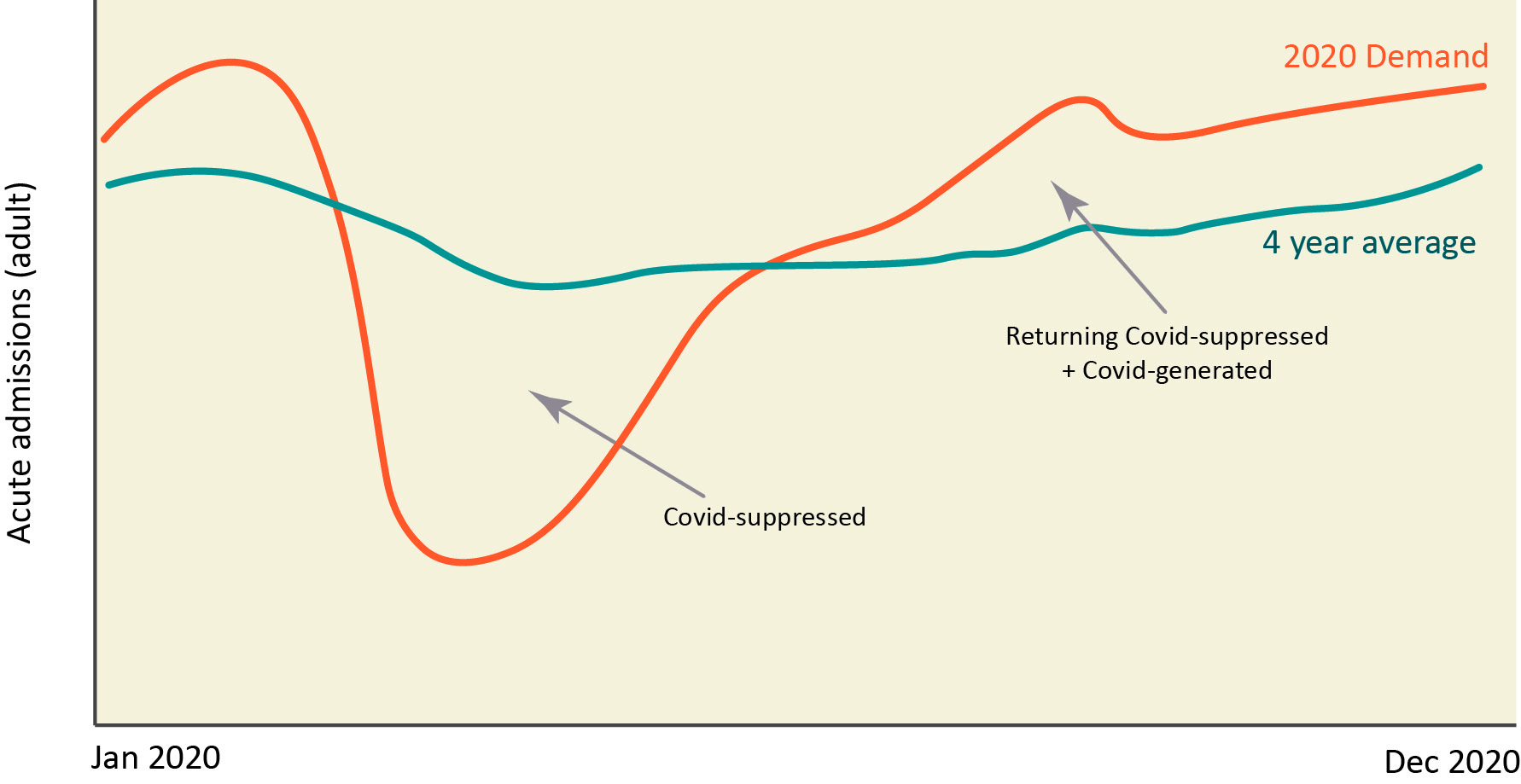

At the start of the pandemic, many NHS mental health providers observed a sudden decrease in demand for services compared with previous years. This led to the consideration of future demand presenting in two ways:

- Covid-suppressed: People who would, had it not been for Covid-19, sought support from mental health services, and who have temporarily postponed their engagement. It is assumed these people will return to services over time.

- Covid-generated: people whose experiences of Covid-19, both directly and indirectly, have caused them to develop a degree of mental illness. (These individuals will not have been referred to services had Covid not occurred.)

Fig 1: Potential surge in demand for mental health services as an impact of Covid-19

Following the first wave and the end of national lockdown 1, many NHS mental health provider organisations observed an increase, over and above previous years’ trends, in people presenting with acute mental health problems. This suggests that those experiencing severe mental illness will present early for support following the relaxing of lockdown restrictions.

Fig 2: Inpatient admissions to mental health services (average for a sample of five NHS organisations)

For those with mild to moderately severe mental health conditions, the picture is somewhat different. These individuals have yet to present at forecasted levels. In fact, demand has not yet returned to pre-Covid levels.

The assumption is that the need for support in mental health has increased during the pandemic, but has not yet reached services. There remains a still-growing cohort of suppressed demand. The exception to this appears to be in children’s mental health, where some providers have seen increased demand for services over and above the levels seen in previous years.

Fig 3: Access to community mental health services in 2020 compared to the four-year average (average for a sample of five NHS organisations)

Mind the gap – the challenge with planning assumptions

Another positive consequence of Covid-19 has been an increase in programmes of work aimed at forecasting the future demand for mental health services as a result of the pandemic.

This forecasting work has mostly occurred collaboratively, with several NHS mental health commissioner and provider organisations coming together, working with colleagues from public health and the voluntary sector.

These combined efforts have produced a range of credible modelling tools. These draw upon the clinical evidence base and generate forecasts in mental health demand, which are being used to support local strategic planning decisions at organisational and system levels.

Forecasts generated by these models indicate that the demand for services would exceed the overall capacity that services have available. Furthermore, whilst models provide forecasts for total future demand, an area that has proved challenging to predict is precisely when that demand will materialise.

Predicting the future – hard to do with current transactional focus

Despite the best efforts of many organisations, there currently remains no nationally agreed forecast for the increase in demand for mental health support. The focus has remained mostly on Acute care.

Current national models use discrete activity planning assumptions, i.e. what can be delivered for a set budget and time. The result is a widening of the gap between real long-term demand (based on actual need) and what services can deliver.

Further undermining the national planning process is the assumption that investments can readily convert into the workforce, with little consideration for the impact of recruitment lag. Add to this, the fact that organisations are each attempting to recruit from the same pool of staff and the workforce challenge becomes compounded.

All these challenges together, make planning exercises prone to being transactional and unrealistic.

System response leading to silo working

Meeting the mental health needs of people requires a holistic approach across the system. During the pandemic, the NHS moved in to control and command from the Centre, with cell and sub-cell arrangements.

Whilst this was necessary to mobilise a national emergency response, this has had an unintended consequence of maintaining silo working and perpetuating fragmentation across health systems.

Although the pandemic has accelerated the pace of collaboration among partners across the system, there remains a tendency to compartmentalise mental health, i.e. the physical/mental health divide.

NHS mental health provider organisations have started to look ahead to 2021/22. There will soon be a requirement for them to formalise their plans as part of national ‘Phase 4’ planning. It is expected, however, that the planning approach to mental health will again be separate and stand-alone, with a short-term, transactional focus.

This is a missed opportunity. There needs to be a shift from focusing on transactions/activities to meeting the holistic needs of the individual’s health and wellbeing.

The need for space to innovate and build for the future

Understandably, the focus of management and Boards is on delivering the intense national and regional response to the pandemic. We have also seen some fantastic innovations and ways of working. But the challenge for management is to ‘bottle’ and scale these innovations as systems come out of the current pandemic.

There is also the drive to digital. But we must do this carefully and considerately as some service users will require face to face support and a human presence, particularly with therapeutic interventions, such as occupational therapy. Digital-only solutions will, for some, not be sufficient.

Leaders will need to create enough safe space to allow innovation to be tested and developed.

Five recommendations in moving forward

We recommend mental health planners and strategists should:

1. Model ‘true’ demand: national approaches have focused on increasing capacity, with little consideration regarding whether this increased capacity will be enough to meet future demand.

There should be an ongoing focus, supported nationally, building on the excellent forecasting work commenced by several organisations, to assess and refine future forecasts continually. This practice should become the established norm and continue beyond the pandemic to continuously evaluate the nation’s future mental health needs.

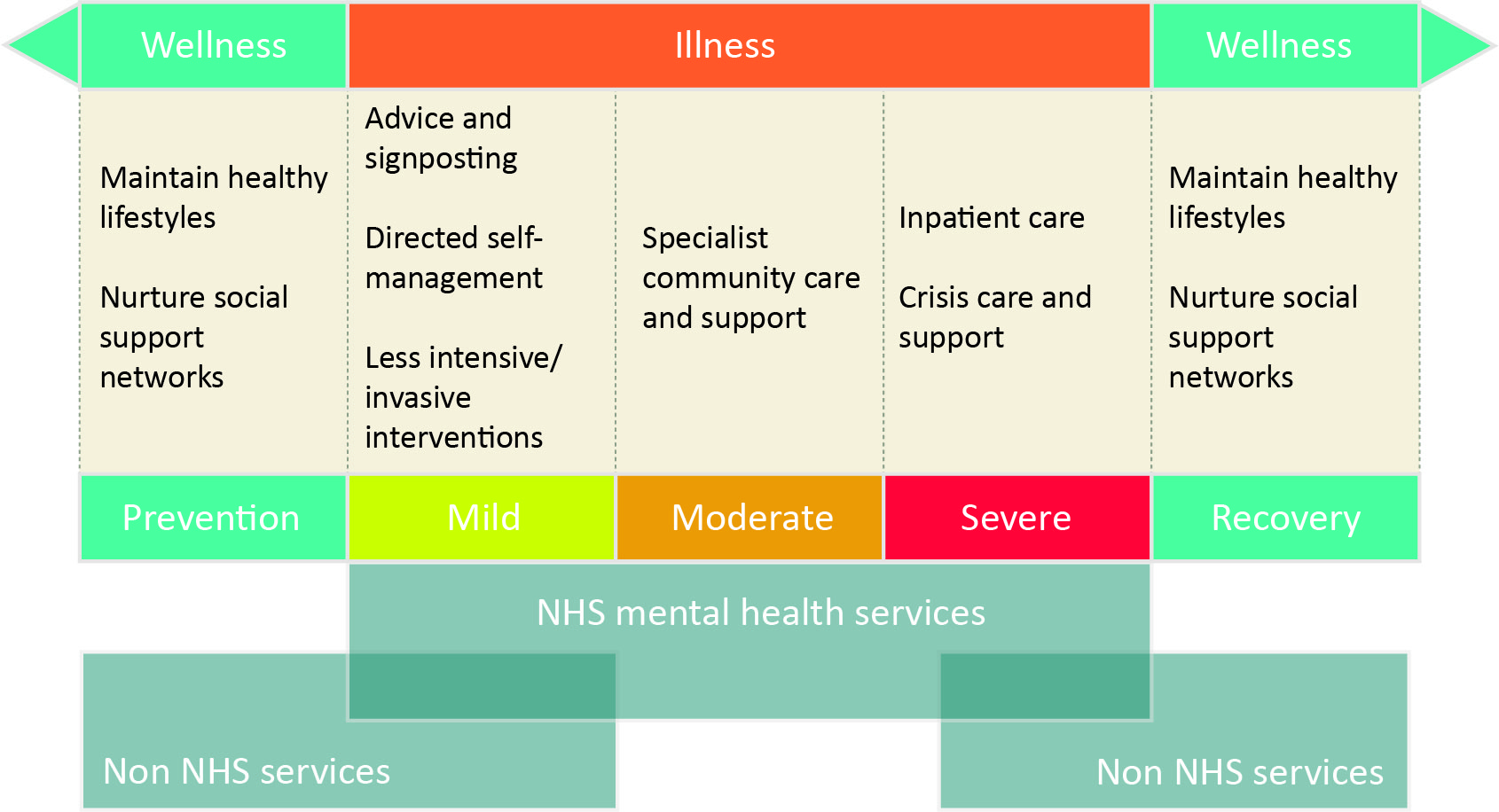

2. Refocus on individual needs, not services: health systems and mental health organisations must take the opportunity to reimagine the transformation of services around the needs and wants of the population. The current planning approaches and tools are mostly ‘technical’ and aggregation exercises. Patient needs are often limited to references to national policies or local public health reports.

There needs to be a shift to thinking about the patient experience rather than maintaining services. They need to be involved in the process. A good test would be, how much of a trust’s board’s time is spent on discussing operational versus service user needs, and which metrics are used to measure success.

3. Develop a single provider and partnership narrative: each provider’s position needs to be transparent concerning who will provide what, to meet the needs and wants of the population. There needs to be clarity on the area where care, support and interventions are to be provided in partnership, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Partnerships should also extend to include local populations, viewing our communities as assets. The focus should be on enabling people to develop supportive social networks that sustain positive mental wellbeing and prevent mental ill-health.

Fig 4: Provider alignment across the wellness-illness-wellness continuum

4. Reimagine access: We need to increase access to, and raise the profile of, mental health support in a way that fits with the population’s changing needs. The pandemic and its effects have been with us for some time, and economically the outlook is bleak. If we do not increase access soon, then demand will continue to accumulate to levels that could overwhelm services.

We should also explore more innovative ways of engaging people who could be more vulnerable to mental illness due to the consequences of the virus. For example, partnering with financial services organisations to offer signposting, advice and support for those affected by economic hardship to better meet people’s needs.

5. Build the future workforce: a clear national plan is needed concerning the mental health workforce, working with other agencies, such as educational establishments, basing future workforce requirements on forecasted demands. There needs to be the continued development of new job roles, e.g. peer support workers, community connectors, and social prescribers.

As ‘anchor’ organisations that exist in every community, the NHS has the opportunity to offer employment opportunities to local populations that have been impacted by the economic upheaval. The chance to rethink social contribution and cohesive communities provides an opportunity to think through more sustainable approaches to address the mental health challenges.

Let’s not waste the opportunity

We should not miss this once in a generation opportunity to modernise and improve mental health services. Our observation is that planners are continuing with existing practices. Leaders must take this opportunity to innovate and break from the old ways, bureaucratic processes and centralisation.

The response to the mental health challenges we face requires a truly strategic approach, to engender service collaboration and integration, and genuine engagement with local communities to develop sustainable solutions.