Health and social care systems need to “rethink” mental health services and not overlook the long-term negative consequences of Covid-19 on people’s mental health

Covid-19 has left no life untouched, no family undivided, no daily routine unaltered. Each and every one of us is learning how to adapt, how to cope, or simply how to be, in these troubling times.

The current focus of the government and the health service, quite rightly, is on the virus itself; on controlling its spread, and on taking care of those who have fallen ill with the disease. Each death is a tragedy. Whilst the response is focused on the short-term, we should not overlook the longer-term negative consequences of Covid-19 on people’s mental health.

Covid-19 will significantly increase an already growing mental health burden

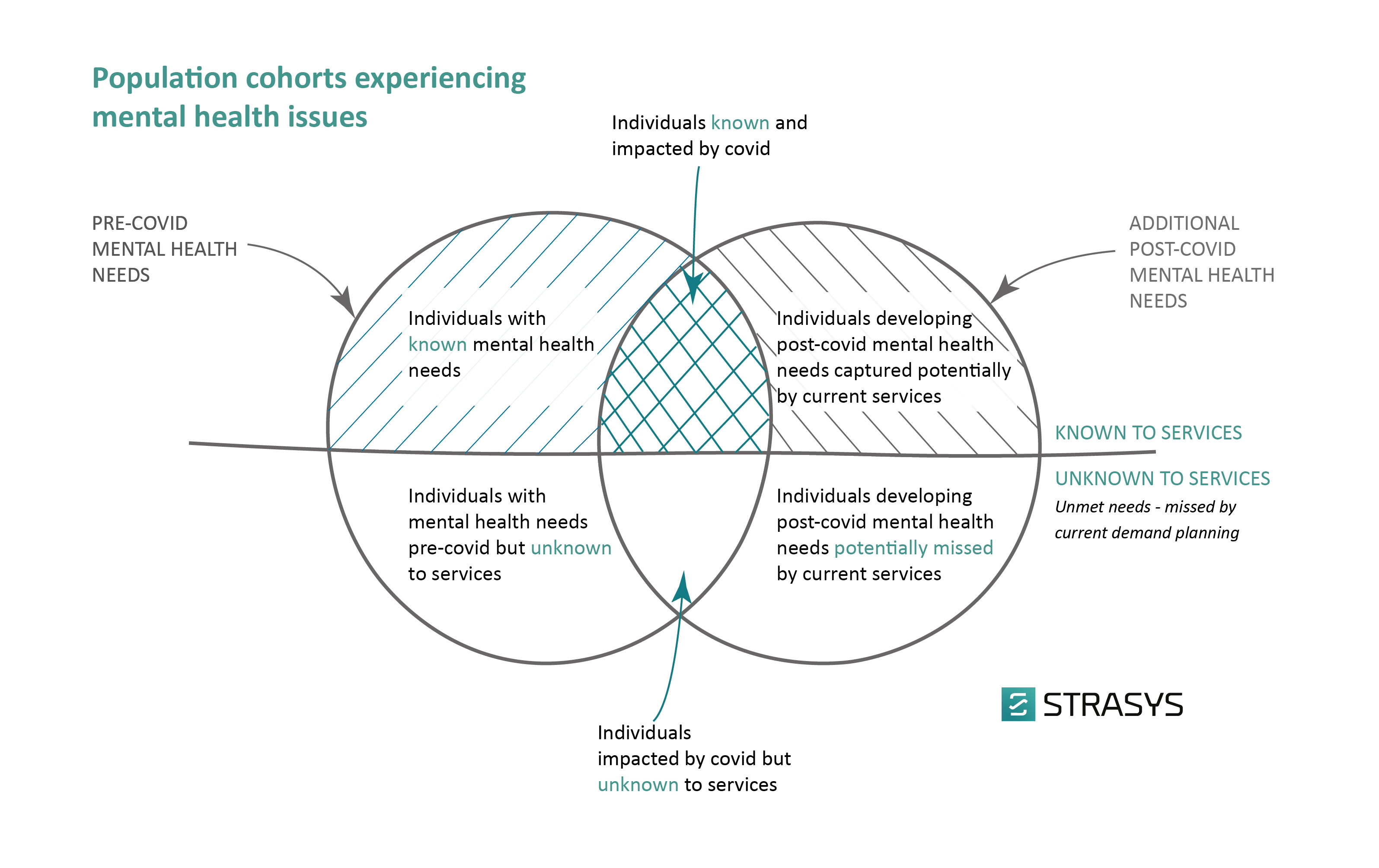

Before Covid-19, it is estimated 1 in 6 of people over the age of 16 had a reported common mental health problem. The number of individuals experiencing mental health problems is probably much larger. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) 35-50% of people with severe mental health problems go unreported and receive no treatment at all.

The mental health incidence rates will increase due to Covid-19. We are already seeing reports of a significant increase in mental health symptoms; the short-term impact of dealing directly with the virus, and longer-term indirect impacts. A study carried out on young people with a history of mental health needs living in the UK reports that 32% of them agreed that the pandemic had made their mental health much worse.

Fig 1: Population cohorts and determining the demand for mental health services post Covid-19

There will also be new segments of the population with Covid-19-related psychological distress. The Lancet Commission on Global Mental Health and Sustainable Development, states that “many people who previously coped well, are now less able to cope because of the multiple stressors generated by the pandemic”. Healthcare workers providing frontline services, as well as people who have lost loved ones or jobs due to the disease, are now at greater risk of developing long-term difficulties. For example, in China, healthcare workers have reported high rates of depression (50%) and anxiety (45%).

Individuals recovering from Covid-19 will also need significant mental health support. After the SARS outbreak in 2003, both healthcare workers and people who were self-quarantined exhibited symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Those who struggle with other mental health conditions, such as anxiety or depression, or who have a prior history of trauma, may be at increased risk of more ongoing distress.

There are also immediate repercussions due to the interruption in mental and physical health services. Some NHS Trusts have seen a drop of 60% referrals to therapy services and a 30% decrease in admissions of seriously ill patients. In other words, we are “storing” the problem.

Health and social care will need to adopt a systems approach

Addressing mental health and wellbeing needs post Covid-19 will require more than just health interventions. It is now beyond doubt that mental health is strongly influenced by social and economic conditions.

Major economies including the UK are on the cusp of a major economic recession. The unemployment rate is estimated to double to 2.6m people in the UK. A potentially long-term period of austerity will be forced upon the government to meet the costs of the Covid-19 economic support packages. The economic outlook is bleak, and it will undoubtedly impact the future funding of health services.

Following the 2008 financial crisis, successive governments adopted austerity measures to respond to the economic shock. This included a reduction in spending on health and social care services. The ensuing economic recession simultaneously weakened factors that protect people from mental ill-health, such as job security, personal relationships, and welfare protection, while increasing some significant risk factors for mental ill health, namely, unemployment, levels of personal debt, and loss of socio-economic status. There are fears that this is likely to be repeated with a much greater impact.

Solutions will require wider socio-economic and community interventions as well as health. Organisations will need to think differently and move beyond meeting individual institutional concerns to a more collaborative approach that puts the needs of an individual at the heart of services. Otherwise, we risk causing more suffering than the virus itself.

Learning from the past in planning for the future

The concept of ‘parity of esteem’ – the NHS objective to put mental health on par with physical health – was enshrined into law in the 2012 Health and Social Care Act. Yet this has not addressed the historical disproportionate lower spend on mental health compared to physical health counterparts.

In 2018, the government attempted to provide more certainty through a five-year funding commitment, providing the basis for longer-term strategic planning. Although the ask of each part of the NHS in England was to develop a strategy, what most systems produced was in fact a five-year operating plan, absent of any strategic thinking on how best to meet the health and wellbeing needs of their respective populations.

Traditionally, planning rounds and the allocation of funding, take place annually without a tangible long-term system plan. This compels health care planners to be reactive, and conditions managers and clinical leaders to focus persistently on the here and now, clouding them from the longer-term consequences of their actions.

A key challenge in the NHS has been the bureaucratic approach to planning. There is a short-term, operational, service, and transactional focus, which in turn leads to tactical thinking at the expense of strategic planning for the long-term. It is only human nature that managers and boards get consumed in executing plans and meeting targets with a sense of achievement.

Strategic thinking has never been more critical if we are to navigate through the current crisis and alleviate longer-term repercussions of Covid-19 for people’s mental health.

An opportunity to build back better

Few longitudinal studies exist in the UK that examine the damage to mental health on the wider population caused by periods of economic hardship, and there is a need for better empirical studies.

In the meantime, the rapid and commendable response from the NHS in dealing with the sudden onset of Covid-19 should be coupled with longer-term strategic planning to support those who experience the impact of the disease, directly or indirectly, through a deterioration in their mental health.

The NHS, with support from the government, needs to free itself from habitual short-termism. We need to tackle the prevailing threat from Covid-19, as we are doing now, while at the same time taking a long-term strategic view to manage the unintended consequences of lockdown and isolation measures on people’s mental wellbeing.

We need to stop taking a service perspective and put the needs of the population at the centre of our thinking. This is the fuel for disruptive innovation.